The History of Netrek, through Jan 1 1994

[ This file is still incomplete; I will add more as time allows. ]

- 0. Introduction

- 1. Pre-History

- 2. Xtrek

- 3. Xtrek: The Next Generations

-

4. Expansion

- 4.x KSU

- 4.x CMU

- 4.x Usenet

-

5. Renaissance

- 5.x Robots and borgs

- 5.x Server Tools and Toys

- 5.x The INL

- 5.x UDP

- 5.x Meta-servers

- 5.x RSA

- 5.x Other Leagues

-

6. New Directions

- 6.x Sturgeon

- 6.x Hockey

- 6.x Paradise

- A. Contributors

0. Introduction

0.1 What's the Point?

A few people have asked me why I decided to do this, and more than a few have suggested that I have too much time on my hands. Fact is, there are probably more productive ways to be spending my evenings.However, this is something I've wanted to do for a while. I was at U.C. Berkeley when the game was being developed, but I missed out on most of the early days, after Netrek stabilized and began to spread. Doing this history gives me an excuse to ask people about what was going on back then, and to find out about Netrek's roots in games like Empire.

What finally inspired me to get to work on it was looking at the articles in Wired and in the San Jose Mercury. Each of them included a brief (two or three sentence) history of Netrek, to give their readers some perspective on where the game came from. I expect the number of magazine and newspaper articles on Netrek to increase, and I expect the number of factual inaccuracies to increase proportionally. (If you don't know what I mean by "factual inaccuracies", read the article in Wired, and tell me if what they describe sounds right.)

This, then, is an attempt to write down, once and for all, how it all began. Who wrote it, where it was written, what inspired it, and how it became the game as we know it today.

0.2 What is Netrek?

Just so we're starting off on common ground:

Netrek is a game originally written for UNIX and X windows by Kevin Smith and Scott Silvey. It has no relation to Nettrek, a game for the Macintosh.

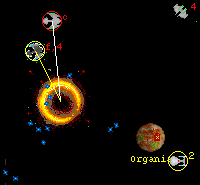

Netrek is a real-time graphical multiplayer arcade/strategy game played over the Internet. Players form into teams and fight for control of the galaxy, dogfighting and taking planets.

0.3 About the Author

It isn't possible to write about history without imposing your own opinions

and views. Even purely factual articles will show their prejudice

according to what is included and what is omitted. For this reason (and

the opportunity to brag my ass off) I'm including a brief description of

my involvement with Netrek.

I showed up at UC Berkeley ("Cal") in the Fall semester of 1987. The WEB cluster (Workstations in Evans Basement) was relatively new, filled with Sun 3/50 workstations running X10. A second lab was upstairs in Evans hall, in room 260. (If you're wondering why some old versions of BSD "chfn" tell you to enter your office number as "260E" or "414C", it's because all the CS and EE offices were in Evans or Cory.)

Besides the usual time wasters, like hunt and this nifty multiplayer strategy game called xconq, there was a game called Xtrek. One night I saw some people playing and asked how to get in. I was told to type the following magic incantation:

xhost sequent

telnet sequent 520

This was the start of a lasting addiction.

The next semester, work on Netrek began. I started playing when the clients became available, and played frequently until a certain female suggested I should spend my free time in other ways.

This affliction lasted until late 1991, after I had graduated and gone to work for Amdahl. There were a few xtrek players there (who used the modifiable ships to create floating phaser platforms that could rip you apart from the other side of the tactical), but Netrek hadn't been ported. So, I ported the client and server, and we had what may well be the first Netrek game played on a 390-class IBM-compatible mainframe.

Since then I've worked on a variety of Netrek projects, most of which are described later.

What you need to keep in mind as you read this is that my *direct* experience with Netrek and its predecessors occurred during the early development stages and in fairly recent times. Anything that I have participated in will have better detail, but a correspondingly greater bias toward my own perception of reality.

For things that I am not directly familiar with, all my information comes from other people's (sometimes conflicting) descriptions of what once was.

The rest of this is written in the 3rd person [except for notes in square brackets], which gets a little weird when I start talking about myself. I've included an indication of who provided information for each major section (e.g. [J.Doe]) in alphabetical order; see the list of contributors at the end of the document for their names and e-mail addresses. Most of the information in this document comes from e-mail correspondence, Usenet postings, and (where possible) personal experience.

I assume you are familiar with Netrek. My goal is to detail its history, not explain the game.

- Andy (ShadowSpawn)

1. Pre-History

1.1 The Dark Ages

In the beginning, there was darkness. People played chess or something.Out of Chaos, PLATO was formed, and it was good.

1.2 Empire on PLATO

PLATO was designed in 1968 by the University of Illinois at Urbana to be a

computer-aided instruction system. It consisted of special terminals

connected over a network to a central CPU. There are somewhere around 2500

sites with PLATO access today.

The terminals featured a 512x512 pixel gas plasma display, a keyboard with several specialized keys, and a connection that ran at about 1200bps with a 150bps backchannel. Not much to look at by today's standards, but very impressive at the time.

The terminals were primarily character based, but with a twist: the characters could be placed at any position on the screen, and the character set could be altered. This allowed programs to download custom fonts to the terminal, and use them to form graphic images. By using fonts with a variety of 16x16 graphic images, programs could do attractive screen layouts on a relatively dumb terminal with a low bandwidth connection.

It also made it possible to write some nifty games.

1.2.1 Birth of an Empire

Entire classes of games were invented on PLATO. A dungeon game called Oubliette inspired Robert Woodhead to write Wizardry. Multi-User Dungeons, which now infest the Internet, effectively began there. And, in 1972, a quaint game of conquest called Empire was written.The first version was written by John Daleske and Silas Warner. (Silas went on to write Apple II games for Muse Software, including Robot War, Firebug, and the classic Castle Wolfenstein.) The game was substantially revised in 1975 by Chuck Miller and Gary Fritz, and has been tweaked and tuned by many others over the years.

Like its descendants, Empire has four teams (Federation, Romulan, Klingon, and Orion, though the Klingons were Kazari until 1991 to avoid legal problems). However, all four teams can (and often did) play against each other at the same time.

1.2.2 Combat

The Empire galaxy has only 25 planets in it. Each race starts with three planets, with 50 armies on each. There are two planets in the neutral zone between the home worlds, and five in the middle; all of these start out neutral. In contrast with Netrek, where you can be deep in enemy territory inside 30 seconds, it took about three minutes to get into enemy space from the average starting position. It also took about 5 minutes for one ship to bomb those 50 armies off.Each race flew ships with different strengths and weaknesses. The Orions were faster but had weaker weapons, Federation and Kazari ships were slower with moderate weapons, and the Romulans were slower still, but with powerful weapons. All four races had devoted followers. The Orions and Federation were the most popular, with over 40 active members on each at one time.

The goal of Empire is a familiar one to Netrek players: conquer the galaxy by dropping armies on planets, killing anyone who gets in your way. The means were quite different, however.

First, the ships didn't move in real time. They "built up" time, and then moved when a "replot" command was issued. If you did a "replot" and had no time left, you were a sitting duck until you built up more time. It was common for players to build up time, change course quickly, replot, and then "hyper-jump" (using a large amount of accumulated time) on the new course. When in combat, players had to mentally keep track of how much time their opponents had built up, so that they could figure out which ones were likely to strike.

Second, the weapons were much harder to use. Torpedoes weren't effective outside of 500km, which worked out to be about 0.3 inches. They moved slowly and could be detonated without damage to the attacked ship outside that range. Phasers were an area-effect weapon, but required that the angle of the shot be entered in degrees, and weren't effective outside of a narrow arc (phasers were drawn, slowly, as two lines emanating from your ship). Since the computer mouse hadn't been invented yet, all commands were entered via the keyboard.

Dogfighting was an exercise in physical dexterity and mental calculation, as players computed phaser angles and tried to pounce on each other with torpedos while avoiding attackers. In close combat situations, player typing speeds often exceeded 300 words per minute. Several 15-on-15 games were played, often lasting a full six hours, requiring a great deal of stamina.

A game of this intensity is bound to cause friction between the players. At one point, a Romulan systems programmer threw Coke at a Klingon team member, and was subsequently banned from the game. In another incident, a Klingon player threw a chair at an Orion. Reports of shouting matches and scuffles between Netrek players are, therefore, nothing new.

In 1981, Steve Peltz wrote a tournament version of Empire. This provided for formal yearly tournaments, which were largely won by the Orions.

1.2.3 Today

There are often over 700 simultaneous users on the PLATO system today, and Empire is still played. PLATO terminal emulation software exists for the X window system, suggesting the possibility that Netrek players could get a taste of Empire itself. However, the University of Illinois recently sold the rights to PLATO to a private firm, so the future of PLATO and Empire is uncertain.[F.Gallo] [S.Peltz]

Jef Poskanzer, who would later be widely known for his pbmplus utilities,

rewrote the game from scratch for VAX/VMS. He got the planet layout by

spending an afternoon doing a galactic survey, and got the ship

characteristics by flying them around and observing rates of travel and

fuel consumption.

Because the game was played on a standard 80x24 ASCII terminal, the special

PLATO character set couldn't be used. However, roughly the same amount of

information was displayed on the screen, making it a reasonable facsimile

of the original. The bottom few lines of the screen were used for status

messages, and the leftmost dozen columns were used for ship status

information. The right corner could be toggled between a tactical display

and a strategic map.

Poskanzer was joined by another programmer, Craig Leres, who did many

significant enhancements and bug fixes, and eventually took over most of

the development. Conquest's features soon grew beyond those of the

original Empire.

Robot ships were added to protect planets against off-hours bombing. These

used a rule-based AI system that could be changed on the fly, and were

extremely difficult to kill.

Conquest also saw occasional visits from a planet eater [a mega-Iggy],

which was rumored to be in Empire as well.

The "conqnews.doc" file found in the source distribution is interesting

because it shows how some of the features that Netrek players take for

granted got added to the game. Here's a small sample:

[E.James] [C.Leres] [J.Poskanzer]

Trek82 was based on what Davis remembered of Empire. His first attempt at

a game was a single 1700 line C program. It used the UNIX "curses" package

to draw ASCII characters on a standard terminal. Since shared memory

wasn't available in the versions of UNIX available at the time, Davis used

a shared file instead, with each process writing into a specific area of

the file.

Before long, Computer Science department staff member (and former

undergrad) Chris Guthrie took an interest in his work. Guthrie introduced

Davis to Jef Poskanzer and Craig Leres, who were busily working on

Conquest at the time.

Taking some ideas from Conquest (including facets of Empire that he had

forgotten about), Davis created an enhanced version of trek82, called

trek83. As Davis was still relatively new to C programming, Guthrie

helped with the design, cleaned up the code, and added some additional

features.

A year later, in May of 1984, a new version called ROBOTREK was written by

Nick Lai. Trek83 was hacked so that his robots were sent in to play on

empty teams, so that people wanting practice would automatically have

targets. Multiple robots could be sent in, allowing for robotrek battles.

[D.Davis] [C.Guthrie] [E.James] [B.Johnson]

1.3 Conquest

Addiction to Empire was common and difficult to break. In 1982, a

programmer who had become addicted six years earlier decided to recreate

Empire outside of PLATO.

1.3.1 Familiar Differences

Poskanzer chose VMS over UNIX because, at the time, UNIX lacked shared

memory facilities. His design for Conquest differed significantly from

Empire with the addition of an independent daemon process that did

updates 10 times per second. This meant that everyone played in real

time, so hyper-jumps were no longer possible.

1.3.2 Status

Two distributions of Conquest were done via DECUS, in September of 1983

(VAX-72, V-SP-23, or VAX-LIB-2) and in 1986 (V-SP-61). It's not known

how widespread the game became, or how much of a following it attained.

It's clear, however, that many of the ideas from Conquest found their way

into Xtrek and Netrek.

1.4 Trek82 and Trek83

At about the time Conquest was being written, a UC Berkeley student

named David Davis began writing a UNIX game called trek82. He had

used the PLATO system while at the University of Hawaii, and had been

impressed by the multi-player games.

1.4.1 Robotrek

After trek83 was made available, other UCB students joined in. Ed James

decided it would be interesting to add automated players to the game. The

robot he wrote was essentially a cyborg; the player could toggle between

manual control and robot mode.

2. Xtrek

2.1 The Dawn of Xtrek

Sometime in the mid-1980s work began on the X window system. The first

generally available version of X was X10 release 3, in February 1986.

What made X different from other window systems was its licensing, which

allowed free distribution and porting to different architectures.

At about this time, Chris Guthrie (now a staff member for the CAD group) began designing a successor to trek83, using ideas from both it and Conquest. He called the game Xtrek, because the interface used X windows instead of ASCII text.

Xtrek was a major step up visually from trek83 and Conquest, because of the high-resolution color graphics available on most X workstations. It also represented a major change in player interaction, because the addition of the mouse as an input device allowed fast action without requiring that the player be an excellent typist.

The game was designed and largely written by Chris Guthrie. Ed James worked on some of the graphics code, designed the original ship and explosion bitmaps, and developed server robots for Xtrek much as he had for trek83.

At around the time Xtrek was being developed, an organization called the Experimental Computing Facility (XCF) was formed by a group of hackers with the support of some UCB professors. In exchange for working on useful software projects, the group was provided with a small room (the XCF "fishbowl" in cory hall) and some machines to work on. Although it was never an official project, several members of the XCF - which included Chris Guthrie, Ed James, and Nick Lai - contributed heavily to Xtrek.

2.1.1 Features

It may be unfair to describe Xtrek as a subset of Netrek, but that's the easiest way to go about it. Xtrek looked very much like Netrek, though the planets were in slightly different positions, and several of them had different names. There was only one kind of ship, which felt like a hybrid between a Netrek CA and DD. There were no tractor beams, no plasma torpedos, and when you cloaked your ship simply vanished. Players often stuck something onto the screen to mark their position so they could tell exactly where they were while cloaked.At one point during play testing, Ed James got tired of people bombing 3rd space to get kills for taking planets. As in Netrek, players received partial kills for bombing armies; the weenie way to get a kill was to wander off into undefended territory, bomb a few planets, and then use the kill to take. So, James modified the server daemon to send in server robots when an undefended planet was bombed.

[I couldn't figure out why the original Netrek daemon didn't send in a robot when somebody just dropped armies on a planet without bombing... you could take a planet in 3rd space without a robot coming after you. Now I understand: it wasn't meant to stop people from *taking* 3rd space, just bombing.]

2.1.2 Architecture

The Xtrek server used a shared memory segment to communicate between processes. Like Conquest, it had an independent game daemon that updated everything 10 times per second, advancing ships and torpedos, checking for collisions, and marking players as dead. For each player, a separate "xtrek" process updated the display and took user input.An important distinction (perhaps THE distinction) between Xtrek and Netrek is the way the server sends information to the player. In Netrek, every player has a client program that connects to the server. For Xtrek, the server process acts as an X client, driving the display directly. This meant that there was no "client" for Xtrek; the player connected to an Xtrek daemon (written by XCF member KJ Pires) with telnet, and asked to either play, copilot, or watch (no wait queues, neither).

Because the server acted as the X client, all of the X10 updates had to be sent over the network. This was perfectly satisfactory within the UC Berkeley CAD group where it was designed, and performance was acceptable to other parts of the Berkeley campus unless a lot of people were playing in one area. The original server was "janus", a CAD group VAX, followed by "eros".

2.1.3 Playing Styles

Many of the Xtrek games played at UCB were almost devoid of strategic considerations. The only relative measure between players was the total number of kills and kill ratio (i.e. the ratio between the number of times a player killed someone else and was themselves killed). This caused many players to ignore planet taking and devote themselves exclusively to killing members of the other team.It is ironic then that the Xtrek architecture made dogfighting so difficult. Most Xtrek-playing undergrads at UCB used Sun 3/50 workstations in the WEB or in 260 Evans hall. The workstations in the clusters had no local disks (the NFS servers were at - and often over - their limits), only 4MB of memory, and were shared by hundreds of students. Transmitting X10 traffic over a network under these conditions produced marginal success at best.

No history of Xtrek would be complete without mentioning Peter Moore, a graduate student in the CAD group who played as Pink Puppy. Moore would have been an amazing player even with the limitations of the WEB. However, he had a microvax to himself on a different part of campus, and so didn't have to suffer every time somebody's copy of emacs got swapped out on the diskless workstations. He was, in a word, unstoppable.

2.1.4 The First Tournament

The first Xtrek tournaments were fought between the CAD group and the XCF. The CAD group had the technological advantages: they played on the same subnet as the server, used microVAXes with hardware mice (the XCF used Suns, so the cursors froze up when the machine load got too high), and most or all of them had color monitors.However, the XCF team had a powerful advantage as well: they all played in the same room, making coordination easier. The CAD group players were spread out across several rooms. In addition, the XCF players had a full-time coach who would make sure players were aware of important events in other parts of the galaxy.

Two tournaments were held, both won by the XCF. During the first tournament, the CAD group was steadily wearing down the XCF team. The teams had been in so many games together that the CAD players knew exactly how to deal with each XCF member. Part way through the tournament, KJ Pires came up with an interesting idea: switch machines. Each player moved one machine to the right. Suddenly, every XCFer had a different style and different set of tactics. The CAD group didn't know what hit them until the game was over.

[C.Guthrie] [E.James] [S.Silvey] [J.Wallace] [Xtrek manual & source code]

2.2 Xtrek Today

Several people have done X11 ports, including Chris Guthrie himself. Guthrie

released Xtrek 6.0 in January of 1992 after a resurgence of interest in

the original.

A different version, Xtrek 5.4, was written by Mike Bolotski, Jon Bennett, David Gagne, and Daniel Lovinger, with some stuff by Jim Anderson, John Myers, and Joe Keane. Besides the port to X11, it featured a server configuration file that allowed the different races to have different kinds of ships, as in Empire.

Xtrek was played at Berkeley at least through 1989, when it was part of a rotation with Netrek and XtrekIII. Eventually it was removed from the rotation because the other two games were far more popular. An old Usenet posting indicates that a modified version of Xtrek was still being played at CMU at least through November of 1991.

[C.Guthrie] [Xtrek manual(s) & source code]

3. Xtrek: The Next Generations

3.1 Xtrek-II

In early 1988, UC Berkeley student Scott Silvey began playing with the sources for Xtrek version 4.0. He wanted to add more depth to the game to enhance the strategy and teamwork aspects of it, so he started by adding different kinds of ships (light, medium, and heavy).Like other Xtrek hackers before him, Silvey joined the XCF, where he continued to add features and tweak parameters. Before long, he was joined on the project by fellow undergrad Kevin Smith.

While Silvey continued to add features like starbases that you could dock on, plasma torpedos, tractor beams, and AGRI planets, Smith enhanced the control and display with features like mappable keys, improved player listings, and a player database.

Xtrek-III had some innovative features, some of which didn't surface in

Netrek until recently (e.g. transwarp, absent until late 1993). Among

them:

What finally set Xtrek-II apart from the others were two major enhancements

added by Smith: separation of the code into client and server components,

and the introduction of the DI system.

Smith added network code that separated the game into distinct client and

server components. Each player ran a client program that communicated with

the server using a vastly simpler protocol. The client handled all

rendering locally, so the bandwidth requirements were greatly reduced.

The server architecture remained largely the same, with a single daemon

process and one server process per player. However, the server processes

no longer drove the display, so the Xtrek-II server became independent

of the X window system.

As time went on, Silvey and Smith decided that calling the game "Xtrek"

no longer made sense, since it wasn't bound to X windows. Since it could

be played over distant networks, they called it Netrek.

However, Smith liked the idea of ranks, so in the Fall of 1989 he added the

concept of Destruction Inflicted (DI). This took planet taking and bombing

into account as well as kills and deaths. Ranks were added, and promotions

were based on the new player ratings and the amount of time the person had

spent playing.

To prevent rapid rank advancements in games with only two or three people

in them, Smith created Tournament Mode (T-mode). Only actions taken during

T-mode counted toward DI and rank advancement.

While there has been much debate over the usefulness and worth of the DI

system, it represented a dramatic improvement over Xtrek-III (which was

arguably a big step backward). To this day, no one has come up with an

alternative scheme that is generally regarded as an improvement.

As a debugging aid, Silvey and Smith added a new kind of ship, the "ATT".

Silvey used the AT&T "death star" logo for the bitmap as a joke about the

conflict between BSD and System V UNIX. Originally the ship didn't appear

in player listings and was completely invisible when cloaked, but these

changes had to be done away with for game security reasons when the

client/server modifications were made.

Other features were removed as well after. Co-piloting of ships carried

over from Xtrek, with no restriction on the number of copilots. In one

game Silvey and Smith were part of a four-man crew, where one player fired

phasers, another fired torpedos, another dodged, and yet another sent a

constant stream of insults at the nearest player. It was extremely

difficult to dogfight a ship with so many pilots. [ In the old "scam"

sources, there was a race condition that could cause two players to end up

flying the same ship unintentionally. It provided for some colorful

moments. ]

As people began hearing about Netrek, Smith and Silvey started getting

requests for the source code. After sending it to a few people, Smith

decided to post it to Usenet in late 1989, and it spread quickly.

Xtrek-III was written for X10 and never ported to X11. It's not known

whether anyone outside of UC Berkeley has played it.

[T.Holub] [S.Silvey] [K.Smith]

3.2 Xtrek-III

After Xtrek-II was well under way, XCF member (and Robotrek author) Nick

Lai began working on a new version with UCLA student Jon Edwards. Since

"Xtrek-II" was already in use, it was referred to as "Xtrek-III".

The ranking system deserves some attention. Many Netrek players complain

bitterly about the DI system, since it places emphasis on scumming

planets. Here's how rank was determined in Xtrek-III:

Total Max Ratio Rank

Kills Kills

0 0 0.0 Ensign

20 3 0.5 2nd Lieutenant

100 5 0.75 Lieutenant

200 5 1.0 Lt. Commander

300 7 1.5 Commander

400 10 1.75 Captain

600 14 2.0 Commodore

800 18 2.5 Rear Admiral

1000 25 3.0 Admiral

1250 30 4.0 Fleet Admiral

1500 50 6.0 Grand Admiral

Because of this, most players spent all their time trying to kill the

weakest opponents while not dying. The original Xtrek had the same

measures of performance, but since it didn't keep them in a player database

there was no incentive to maintain a high ratio game after game.

3.3 Netrek

Many of the basic enhancements found in Xtrek-III are similar to those

initially developed for Xtrek-II. However, some of the features in

Xtrek-II came straight out of Xtrek-III. For example, Smith took the

gas/wrench/man planet bitmaps from there, as well as the idea for limited

visibility on the galactic map (though it's not quite as restrictive in

Netrek).

3.3.1 Client/Server

Recall that Xtrek handled all rendering from the server side. The X10

traffic was sent over TCP sockets from the server to the player's display.

3.3.2 Destruction Inflicted

One feature that Netrek lacked was an effective scoring system. Smith

added a database so players could choose a pseudonym to play under and have

their configuration (keymap and various defaults) preserved by the server.

Unlike the Xtrek-III database, it didn't record kills and losses, because

Smith hated the butt-torping scum-fests prevalent on Xtrek-III servers.

3.3.3 Further Changes

Silvey and Smith continued adding features and fixing bugs for some time.

When X11 was released in early 1988, Smith created a system-independent

window interface for Netrek, so that he could encapsulate the differences

between X10 and X11 in a single file. He also did an IRIS GL port for

SGI machines.

3.3.4 The End of Xtrek-III

For a while in 1988 and 1989, Xtrek, Netrek, and Xtrek-III were part of a

rotation on sequent.berkeley.edu. Xtrek was dropped after a while, since

most players were more interested in the newer, more complex games. A

little while after that, Xtrek-III was dropped in favor of Netrek, because

of Netrek's client/server model and improved ranking system.

4. Expansion

[ Want to talk about:

- Guys who set up the server at KSU

- Terence bringing it with him to CMU

- Iggy

- Origin of term "ogging"

- Creation of alt.games.xtrek, rec.games.netrek

]

5. Renaissance

[ Want to talk about: - All the borgs, borg servers, and borg-hours on servers in late '91 - det own torps deliberately allowed individual dets - Server tools and toys - XSG, pledit (Pig Borg trashing server DBs with ^J in keymap...) - "top gun" mode - The INL - Creation (+ first UCB vs CMU match) - INL server, "INL legal" clients - Creation of UDP - Why tried - Banned from INL games 1st season - Creation of METASERVER and MS-II - Introduction of RSA - Formation of INFL, ENL, ANL, INHL, PLC, and whatever else - [need more info] ]

6. New Directions

[ Want to talk about: - Hockey servers - Sturgeon "upgrade" servers - Paradise servers - v1.0 and v2.0 ]

A. Contributors

Contributors to the Netrek History project, in alphabetical order, with a summary of what they provided and their most widely known Netrek name.I have made every effort to recognize everyone who contributed; if I have forgotten someone, PLEASE let me know.

- Kevin Michael Bernatz (kmbst30+@pitt.edu) [Sun Tzu, Akira]

- History of ogging

- Terence Chang (terence@JANET.UCLA.EDU) [Exxon Valdez]

- Bronco history

- Greg Chung (gchung@pegasus.rutgers.edu) [Stiletto]

- Interesting tidbits

- Neil Cook (nlc@computer-science.nottingham.ac.uk) [Drax...]

- Netrek in the U.K., old server lists

- David Davis (ddavis@gain.com)

- Trek82/Trek83 history

- Leonard Dickens (leonard@cs.UMD.EDU) [Wreck]

- Ping clients, NBR

- Robert Forsman (thoth@floater.cis.ufl.edu) [Hammor]

- Paradise info

- Felix Gallo (async@IO.COM) [Sunscreamer]

- SLIP usage, Empire history

- Brandon Gillespie (BRANDON@cc.usu.edu) [Lynx]

- Paradise history

- Dave Gosselin (gosselin@ll.mit.edu) [Tom Servo]

- Vanilla server & borg accusations

- Chris Guthrie (chris@xcf.berkeley.edu)

- Trek82/Trek83/Xtrek history

- Tedd Hadley (hadley@vlsi.ICS.UCI.EDU) [Pteroductyl]

- Dates for some stuff

- Jonathan Hardwick (jch@cs.cmu.edu) [Spaceman Spiff]

- Info on archive site, info on borgs, SLIP usage

- Robert W. Hill (rh3b+@andrew.cmu.edu) [Spaceace!]

- Lots of INL history

- Tom Holub (doosh@netcom.com) [Mojo Riser]

- Early Xtrek/Netrek history, newsgroup creation, INL stuff

- Jack Hsu (jh@cs.UMD.EDU) [Gaia]

- Dates for some stuff

- Ed James (edjames@xcf.berkeley.edu)

- Trek82/Trek83/Xtrek history, e-mail addresses of hard to find people

- Beorn Johnson (beorn@swindle.Berkeley.EDU) [Snidly]

- Early history

- Alex Kluge (kluge@wixer.bga.com)

- UTexas history

- Andrew Markiel (markiel@callisto.pas.rochester.edu) [Grey Elf]

- CMU history

- Brett McCoy (brtmac@ksu.ksu.edu)

- KSU history

- Bharat Mediratta (Bharat.Mediratta@Eng.Sun.COM) [Shade]

- History of game recorders

- ERic Mehlhaff (mehlhaff@soda.Berkeley.EDU)

- History of stuff he'd done

- Hugh Moore (wildman@MIT.EDU or madpit@mit.edu) [ZZnew guy]

- INL history

- Todd Mummert (Todd_Mummert@AUK.WARP.CS.CMU.EDU)

- Pig borg

- Jeff Nelson (nelson@math.arizona.edu) [Miles Teg]

- Borg/robot info, CMU history

- J. Mark Noworolski (jmn@crown.Berkeley.EDU) [Passing Wind]

- INL server history, BRM client history

- Steve Peltz (peltz@cerl.uiuc.edu)

- Empire history

- Jef Poskanzer (jef@ee.lbl.gov)

- Conquest info

- Peter Pregler (Peter.Pregler@risc.uni-linz.ac.at) [The Kid]

- Austrian history

- Joseph Rumsey (jrumsey@mozart.UCR.EDU)

- Amiga client info

- Steve Sheldon (sheldon@iastate.edu) [Caesar]

- Bits of history

- Sam Shen (sls@aero.org) [Buster]

- Collection of 100+ Usenet posts from late '91 on

- Scott Silvey (scott@swindle.Berkeley.EDU) [Mr Clean, BifTheStud]

- Early history

- Kevin Smith (kpsmith@sgi.com) [Smith, Flotsam]

- Early history

- Tetsu Takekoshi (takekosh@scf.usc.edu) [Crunchy Frog]

- Interesting tidbits

- Nick Trown (trown@ecst.csuchico.edu) [Netherworld]

- RSA, guzzler srcs

- Donald Tsang (tsang@austin.ibm.com)

- Sturgeon history

- Brick Verser (bav@hobbes.ksu.ksu.edu) [bav]

- KSU history, several hundred K of Usenet postings

- Jeff Wallace (jeffw@swindle.Berkeley.EDU)

- Xtrek history

- Rick Weinstein (moo+@cmu.edu)

- Moo/ricksmoo/BRM client info, INL history

- Jiang Wu (jiangwu@sickdog.CS.Berkeley.EDU)

- History of bigdog.cs.berkeley.edu

- Joseph Young (jfy@cis.ksu.edu)

- KSU history